sport.wikisort.org - Athlete

Francis Alexis Patrick (December 21, 1885 – June 29, 1960) was a Canadian professional ice hockey player, head coach and manager. Raised in Montreal, Patrick moved to British Columbia with his family in 1907 to establish a lumber company. The family sold the company in 1910 and used the proceeds to establish the Pacific Coast Hockey Association (PCHA), the first major professional hockey league in the West. Patrick, who also served as president of the league, would take control of the Vancouver Millionaires, serving as a player, coach, and manager of the team. It was in the PCHA that Patrick would introduce many innovations to hockey that remain today, including uniform numbers, the blue line, the penalty shot, among others. His Millionaires won the Stanley Cup in 1915, the first team west of Manitoba to do so, and played for the Cup again in 1918.

| Frank Patrick | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hockey Hall of Fame, 1950 (Builder) | |||

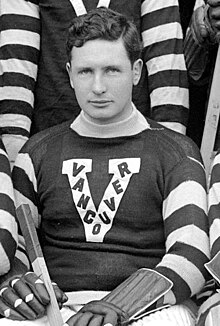

Patrick while a member of the Vancouver Millionaires, 1913–1914 | |||

| Born |

December 21, 1885 Ottawa, Ontario, Canada | ||

| Died |

June 29, 1960 (aged 74) Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada | ||

| Height | 5 ft 11 in (180 cm) | ||

| Weight | 185 lb (84 kg; 13 st 3 lb) | ||

| Position | Defence | ||

| Played for |

Vancouver Maroons (PCHA) Vancouver Millionaires (PCHA) Nelson Hockey Club (WKHL) Renfrew Creamery Kings (NHA) Montreal Victorias (ECAHA) | ||

| Playing career | 1904–1924 | ||

In 1926 the league, which had since been renamed the Western Canada Hockey League and later Western Hockey League due to mergers, was sold to the eastern-based National Hockey League (NHL). Patrick would later join the NHL in 1933, serving first in an executive role for the league and then as coach for the Boston Bruins from 1934 to 1936. His brother Lester Patrick was also a professional ice hockey player, coach and executive.

Early life

Patrick's father, Joe, was the son of Irish immigrants: Thomas Patrick had emigrated from County Tyrone in Ireland to Canada in 1848 and settled in Quebec. Joe was born in 1857 and in 1883 married Grace Nelson. They moved to Drummondville, Quebec where Joe worked as a general store clerk and Grace was a schoolmarm.[1] Drummondville was predominantly French-speaking and Catholic at the time, making the Anglophone and Methodist Patrick family a minority in the town.[2] Patrick was born on December 21, 1885 in Ottawa, Ontario, the second son of Joe and Grace Patrick.[lower-alpha 1] It is not clear why he was born in Ottawa, which was roughly a 5-hour train ride from Drummondville at the time; biographer Eric Whitehead suggested Grace likely needed some specialized care for the birth as the reason for the relocation.[4] In 1887 the family moved 9 miles (14 km) to Carmell Hill, where Joe bought a half-interest in a general store with William Mitchell.[lower-alpha 2] As in Drummondville the town was mainly Francophone, leading the family to learn French.[2] Joe and his partners sold their store in 1892 earning a substantial profit of $10,000; Joe used his $5,000 to establish a lumber company and built a mill in Daveluyville, which was 60 miles (97 km) west of Quebec City.[6] That winter Patrick and his older brother Lester received their first pair of skates.[5] In 1893 the family moved again, this time to Montreal, as Joe expanded his lumber company. They first lived in Pointe-Saint-Charles, a rail district, before moving to the more prosperous suburb of Westmount in 1895.[7] While in Montreal the two older Patrick brothers were first introduced to ice hockey.[8] Patrick attended Stanstead College, a prep school, where he played both hockey football.[9] They also met Art Ross at this time, who became a close friend of both brothers and had an extensive career in hockey.[10]

In 1904 Patrick played his first senior games, with the Montreal Victorias of the Canadian Amateur Hockey League, then the top league in Canada; he recorded four goals in the five games played for the team.[11] While back from school during a break in 1905, he briefly joined the Montreal Westmount club and played two games. Lester was also on the team, and this marked the first time the brothers played together.[12]

Patrick enrolled at McGill University in Montreal in 1906, and joined their hockey team.[13] The next year Joe purchased a tract of land in the Slocan Valley in southeastern British Columbia (BC), and moved the family west to Nelson, British Columbia, a town near the land, to start a new lumber company there. Patrick remained in Montreal to complete his studies, as he had one year remaining.[14] He played with the Victorias as well during the season, recording eight goals in eight games (he missed the final two games due to a shoulder injury). While professionalism had been allowed in the ECAHA at that time, Patrick remained an amateur. He also worked as a referee in league matches, and while he was the youngest official he was considered to be one of the best, the league president at one point calling him the "most competent referee [they'd] seen all winter".[15][lower-alpha 3]

Nelson and Renfrew

In April 1908 Patrick graduated from McGill with a Bachelor of Arts degree and was planning to travel west immediately to join his family and work for the new company. However he injured his leg in a baseball game that spring, which forced him to stay in Montreal until September 1908. On arrival he took up a position as a "timer", overseeing the 200 labourers who fell trees.[16] He also joined Lester on the local Nelson Hockey Club, which competed in a regional league.[17]

The following year the ECHA was replaced by a new top-level league, the National Hockey Association (NHA), which was openly professional.[18] Several teams began to send offers to both Patrick brothers, who had decided to return east for the winter and play hockey there. Among the teams making offers were the Renfrew Creamery Kings, owned by J. Ambrose O'Brien, a wealthy mining magnate, and when Lester received the offer he replied saying he would join the team for $3,000, an exorbitant salary for the era. Surprised by the offer, Lester asked for his brother as well, and Patrick was offered $2,000 to join the team.[19] Along with other high-profile players, most famously Cyclone Taylor, who signed for a reported $5,250,[lower-alpha 4] the team was nicknamed the "Millionaires".[20] Along with several teammates, the Patricks lived in a boarding house in Renfrew during the season, and players were often seen together about town.[21] While Lester was more out-spoken, Patrick was quiet and reserved, though that changed when the topic of hockey came up. He became quite lively and was open about his ideas on how to improve the game, and what type of tactics could be used.[22] Taylor would later recall he was quite impressed by the brothers knowledge and views, stating that "Frank in particular had an amazing grasp of the science of hockey, and they were both already dreaming about changes that would improve the game".[23]

During the 1909–10 season, with Patrick scoring 8 goals in 11 games. though the team failed to win the championship.[24] After the season the Creamery Kings went to New York City for an exhibition series against other NHA teams.[25] Patrick was impressed by both the diversity of people living in the city[lower-alpha 5] and Madison Square Garden. While it did not have an ice-making plant at the time, Patrick was interested enough to make sketches of the arena, and studied it in detail while he was in New York.[27]

The outlandish salaries offered by Renfrew and other teams were unsustainable, and in response the NHA instituted a salary cap of $8,000 per team for the 1910–11 season.[28] Both Patricks had already returned to Nelson, certain their hockey careers were over anyways.[29] They did help build a rink in Nelson, largely financed by their father.[30] Patrick played a few games for Nelson that winter, but was not seriously committed.[31]

PCHA

Joe sold his lumber company in January 1911, making a profit of around $440,000, of which he gave both Lester and Frank $25,000. In a separate transaction Patrick also sold a private interest he had, earning a further $35,000.[32] With this money Joe solicited ideas from his family on what to invest in, and Patrick suggested they establish their own hockey league, one based in BC and that they controlled. It was put to a vote, with both Joe and Frank voting in favour and Lester against, so they agreed to move forward.[30]

The initial plan was to place teams in large cities in Western Canada, with one each in Vancouver and Victoria (both in BC), and one in Edmonton and Calgary (both in Alberta). Issues in finding support for the Alberta-based teams meant that the new league would only be based in BC initially.[33]

Frank and his brother Lester helped found the Pacific Coast Hockey Association, which launched its first season in 1911–12. He played for and managed the Vancouver Millionaires of that league from 1911–1918, winning a Stanley Cup in 1915. He also served as PCHA president until 1924. In addition, he was the owner of the Vancouver Amazons women's hockey team.

NHL

In 1926 the player rights from the WCHL were sold to the NHL, with Patrick taking a leading role in brokering the sale.[34]

Patrick was offered positions with both the Chicago Black Hawks and Detroit Cougars, two expansion teams who had acquired many former WCHL players, but he refused their offers.[35]

In 1933 he was given a position with the NHL as managing director of the league. In this role he would serve under NHL president Frank Calder and oversee the on-ice officials and enforce the rules.[36] Prior to the start of the 1933–34 season Patrick announced he would be working to cut down on the violence endemic in the sport and see stronger punishment for infractions. He also implemented some new rules, including a crease around the goal; allowing players to stop flying pucks with their hands; and a major penalty for touching an official in any manner.[37] In this role Patrick oversaw the suspension of Eddie Shore for his hit on Ace Bailey during a December 12, 1933 game that saw Bailey hit his head on the ice and nearly die. Initially suspending Shore for six games, once it was clear Bailey would live (though he was forced to retire from playing), Patrick increased the suspension to 16 games, the longest in NHL history to that time. Shortly after a benefit game was played for Bailey in February 1934, Patrick resigned his role. It is not clear why he did so, but historian J. Andrew Ross has suggested Patrick was expecting to take over for Calder as president of the league in short order, and left when that was not going to happen.[37]

That off-season Ross, who had been working as the general manager and coach of the Boston Bruins, offered the coaching position to Patrick for the 1934–35 season, so Ross could focus on managing the team.[38] Patrick accepted, earning $10,500 for the season.[39] However the two did not work well, and after two seasons with the team Patrick was let go in 1936, with Ross again assuming the coaching duties.[40] There was also allegations that Patrick was drunk during the Bruins' series against the Toronto Maple Leafs in the 1936 playoffs;[41] Patrick's daughter Francis instead thought he may have had bipolar disorder, though a diagnosis was never made.[42]

Among Patrick's contributions to hockey were the blue line, the penalty shot, the boarding penalty, and the raising of the stick when a goal is scored, which he suggested. He also made a prophecy: "I dream of the day that teams will dress two goaltenders for each game." This became a reality in the NHL in 1964–65.

Later life

Frank Patrick was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame as a builder in 1950.[43] Patrick is also a member of the British Columbia Sports Hall of Fame, elected in 1966.

After his hockey career Patrick had financial issues, which led to him developing an alcohol addiction. Lester tried to help financially, and the NHL provided a $300 per month pension.[44] He also kept working on innovations for hockey, including an unbreakable hockey stick developed with lamination process, however by the time it was finished fibreglass sticks had been created, making Patrick's model obsolete.[45]

Lester died on June 1, 1960 in Victoria.[46] Patrick was not well and was unable to attend the funeral of his brother, and on June 29, 1960, he too died, in Vancouver from a heart attack.[47]

Contributions to women's ice hockey

As early as January 1916, Frank and his brother Lester talked of the formation of a women's league to complement the Pacific Coast Hockey Association.[48] The proposal included teams from Vancouver, Victoria, Portland and Seattle. The league never formed but in January 1917, the Vancouver News-Advertiser reported that wives of the Seattle Metropolitans had assembled a team. In February 1921, Frank announced a women's international championship series that would be played in conjunction with the Pacific Coast Hockey Association.[49]

Career statistics

Regular season and playoffs

| Regular season | Playoffs | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Season | Team | League | GP | G | A | Pts | PIM | GP | G | A | Pts | PIM | ||

| 1903–04 | Montreal Victorias | CAHL | 5 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 0 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1904–05 | Montreal Westmount | CAHL | 2 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1905–06 | McGill University | CIAU | 3 | 6 | 0 | 6 | 0 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1906–07 | McGill University | CIAU | 4 | 6 | 0 | 6 | 12 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1907–08 | Montreal Victorias | ECAHA | 8 | 8 | 0 | 8 | 6 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1908–09 | Nelson HC | WKHL | 5 | 9 | 0 | 9 | 0 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1909–10 | Renfrew Creamery Kings | NHA | 11 | 8 | 0 | 8 | 23 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1910–11 | Nelson HC | BCBHL | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1911–12 | Vancouver Millionaires | PCHA | 15 | 23 | 0 | 23 | 0 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1912–13 | Vancouver Millionaires | PCHA | 15 | 23 | 0 | 23 | 0 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1913–14 | Vancouver Millionaires | PCHA | 14 | 12 | 8 | 20 | 17 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1914–15 | Vancouver Millionaires | PCHA | 16 | 11 | 9 | 20 | 3 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1914–15 | Vancouver Millionaires | St-Cup | — | — | — | — | — | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 0 | ||

| 1915–16 | Vancouver Millionaires | PCHA | 8 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 3 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1916–17 | Vancouver Millionaires | PCHA | 23 | 13 | 13 | 26 | 30 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1917–18 | Vancouver Millionaires | PCHA | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1922–23 | Vancouver Millionaires | PCHA | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1924–25 | Vancouver Maroons | WCHL | 4 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| NHA totals | 12 | 9 | 0 | 9 | 23 | — | — | — | — | — | ||||

| PCHA/WCHL totals | 87 | 65 | 36 | 101 | 59 | — | — | — | — | — | ||||

Coaching

| Season | Team | Regular season | Playoffs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G | W | L | OTL | Pts | Finish | Result | ||

| 1911–12 | Vancouver Millionaires | 15 | 7 | 8 | 0 | 14 | 2nd | Out of playoff |

| 1912–13 | Vancouver Millionaires | 14 | 7 | 7 | 0 | 14 | 2nd | Out of playoff |

| 1913–14 | Vancouver Millionaires | 16 | 7 | 9 | 0 | 14 | 3rd | Out of playoff |

| 1914–15 | Vancouver Millionaires | 17 | 13 | 4 | 0 | 26 | 1st | Won Stanley Cup |

| 1915–16 | Vancouver Millionaires | 18 | 9 | 9 | 0 | 18 | 2nd | Out of playoff |

| 1916–17 | Vancouver Millionaires | 23 | 14 | 9 | 0 | 28 | 2nd | Out of playoff |

| 1917–18 | Vancouver Millionaires | 18 | 9 | 9 | 0 | 18 | 2nd | Won playoff vs Seattle, lost in Stanley Cup Final |

| 1918–19 | Vancouver Millionaires | 20 | 12 | 8 | 0 | 24 | 1st | Lost in playoff to Seattle |

| 1924–25 | Vancouver Maroons | 28 | 12 | 16 | 0 | 24 | 5th | Out of playoffs |

| 1925–26 | Vancouver Maroons | 30 | 10 | 18 | 1 | 22 | 6th | Out of playoffs |

| 1929–30 | Vancouver Lions | 36 | 20 | 8 | 8 | 48 | 1st | Defeated Portland in League Final |

| 1934-35 | Boston Bruins | 48 | 26 | 16 | 6 | 58 | 1st in American | Lost in semi-final |

| 1935-36 | Boston Bruins | 48 | 22 | 20 | 6 | 50 | 2nd in American | Lost in semi-final |

| NHL Total | 96 | 48 | 36 | 12 | ||||

References

Notes

- There were six children in total: Lester, Frank, Lucinda, Edward, and Dora, and a girl who died in infancy.[3]

- Mitchell later became a Canadian senator.[5]

- Whitehead erroneously states the team was based in Ottawa. See Whitehead 1980, p. 48.

- The figure $5,250 comes from Whitehead's biography of Taylor. However Cosentino has suggested the base salary was closer to $2,000, with the rest coming from a guaranteed salary outside of hockey and a bond to ensure he would sign. Regardless, Taylor had the highest salary in hockey history. See Whitehead 1977, pp. 105–106 and Cosentino 1990, p. 73.

- Taylor later recalled Patrick "couldn't get over all the languages he heard spoken during a walk along Sixth Avenue".[26]

Citations

- Whitehead 1980, pp. 9–10

- Whitehead 1980, p. 11

- Whitehead 1980, pp. 10–12, 39

- Whitehead 1980, p. 10

- Whitehead 1980, p. 12

- Whitehead 1980, pp. 11–12

- Whitehead 1980, pp. 13–16

- Whitehead 1980, p. 14

- Whitehead 1980, pp. 24–26

- Zweig 2015, p. 39

- Coleman 1964, pp. 632–633

- Whitehead 1980, p. 6

- Whitehead}1980, pp. 26–27

- Whitehead 1980, p. 39

- Whitehead 1980, p. 48

- Whitehead 1980, pp. 53–54

- Bowlsby 2012, p. 3

- McKinley 2000, p. 73

- Cosentino 1990, p. 56

- Kitchen 2008, p. 165

- Cosentino 1990, p. 76

- Cosentino 1990, pp. 76–77

- Whitehead 1977, p. 110

- Cosentino 1990, p. 171

- Whitehead 1980, p. 82

- Whitehead 1980, pp. 84–85

- Whitehead 1980, p. 85

- McKinley 2009, pp. 62–63

- Whitehead 1980, p. 90

- Bowlsby 2012, p. 6

- Whitehead 1980, p. 92

- Whitehead 1980, pp. 92–93

- Wong 2018, p. 679

- Holzman & Nieforth 2002, pp. 268–269

- Whitehead 1980, p. 179

- Ross 2015, p. 222

- Ross 2015, p. 223

- Zweig 2015, p. 284

- Whitehead 1980, p. 204

- Zweig 2015, pp. 236–237

- Whitehead 1980, pp. 211–212

- Zweig 2015, p. 237

- Hockey Hall of Fame 2003, p. 20

- Whitehead 1980, pp. 249–250

- Whitehead 1980, p. 250

- Whitehead 1980, p. 251

- Whitehead 1980, p. 252

- Norton 2009, p. 120

- Norton 2009, p. 115

References

- Bowlsby, Craig H. (2012), Empire of Ice: The Rise and Fall of the Pacific Coast Hockey Association, 1911–1926, Vancouver: Knights of Winter, ISBN 978-0-9691705-6-3

- Coleman, Charles L. (1964), The Trail of the Stanley Cup, Volume 1: 1893–1926 inc., Dubuque, Iowa: Kendall/Hunt Publishing, OCLC 957132

- Cosentino, Frank (1990), The Renfrew Millionaires: The Valley Boys of Winter 1910, Burnstown, Ontario: General Store Publishing House, ISBN 0-919431-35-6

- Holzman, Morey; Nieforth, Joseph (2002), Deceptions and Doublecross: How the NHL Conquered Hockey, Toronto: Dundurn Press, ISBN 1-55002-413-2

- Hockey Hall of Fame (2003), Honoured Members: Hockey Hall of Fame, Bolton, Ontario: Fenn Publishing, ISBN 1-55168-239-7

- Jenish, D'Arcy (2013), The NHL Centennial History: 100 Years of On-Ice Action & Boardroom Battles, Toronto: Doubleday Canada, ISBN 978-0-385-67146-0

- Kitchen, Paul (2008), Win, Tie, or Wrangle: The Inside Story of the Old Ottawa Senators 1883–1935, Manotick, Ontario: Penumbra Press, ISBN 978-1-897323-46-5

- McKinley, Michael (2000), Putting a Roof on Winter: Hockey's Rise from Sport to Spectacle, Vancouver: Greystone Books, ISBN 1-55054-798-4

- Norton, Wayne (2009), Women on Ice: The Early Years of Women's Hockey in Western Canada, Ronsdale Press, ISBN 978-1-55380-073-6

- Ross, J. Andrew (2015), Joining the Clubs: The Business of the National Hockey League to 1945, Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press, ISBN 978-0-8156-3383-9

- Whitehead, Eric (1977), Cyclone Taylor: A Hockey Legend, Toronto: Doubleday Canada, ISBN 0-385-13063-5

- Whitehead, Eric (1980), The Patricks: Hockey's Royal Family, New York City: Doubleday, ISBN 0-385-15662-6

- Wong, John (2018), "The Patricks's Hockey Empire: Cultural Entrepreneurship and the Pacific Coast Hockey Association, 1911–1924", The International Journal of the History of Sport, 35 (7–8): 673–693, doi:10.1080/09523367.2018.1540411

- Wong, John Chi-Kit (2012), "Boomtown Hockey: The Vancouver Millionaires", in Wong, John Chi-Kit (ed.), Coast to Coast: Hockey in Canada to the Second World War, Toronto, Ontario: University of Toronto Press, pp. 223–257, ISBN 978-0-8020-9532-9

- Wong, John Chi-Kit (2005), Lords of the Rinks: The Emergence of the National Hockey League 1875–1936, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, ISBN 0-8020-8520-2

- Zweig, Eric (2015), Art Ross: The Hockey Legend Who Built the Bruins, Dundurn Press, ISBN 978-1-4597-3040-3

See also

- Notable families in the NHL

- Patrick Arena

External links

- Biographical information and career statistics from Hockey-Reference.com, or Legends of Hockey, or The Internet Hockey Database

На других языках

[de] Frank Patrick

Frank Patrick (* 21. Dezember 1885 in Ottawa, Ontario; † 29. Juni 1960) war ein kanadischer Eishockeyspieler, - trainer und -funktionär, sowie -schiedsrichter. Sein älterer Bruder Lester war ebenfalls ein professioneller Eishockeyspieler. Aufgrund zahlreicher Regeländerungen, die bis heute angewandt werden, wurde Frank Patrick als The brain of modern hockey bezeichnet.- [en] Frank Patrick (ice hockey)

Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии