sport.wikisort.org - Athlete

Dean Edwards Smith (February 28, 1931 – February 7, 2015) was an American men's college basketball head coach. Called a "coaching legend" by the Basketball Hall of Fame, he coached for 36 years at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Smith coached from 1961 to 1997 and retired with 879 victories, which was the NCAA Division I men's basketball record at that time.[a] Smith had the ninth-highest winning percentage of any men's college basketball coach (77.6%).[1] During his tenure as head coach, North Carolina won two national championships and appeared in 11 Final Fours.[2] Smith played college basketball at the University of Kansas, where he won a national championship in 1952 playing for Hall of fame coach Phog Allen.

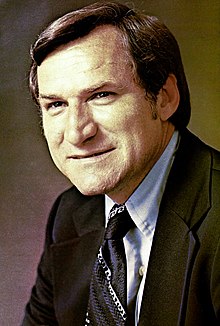

Smith c. 1973 | |||||||||||

| Biographical details | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Born | February 28, 1931 Emporia, Kansas | ||||||||||

| Died | February 7, 2015 (aged 83) Chapel Hill, North Carolina | ||||||||||

| Alma mater | University of Kansas | ||||||||||

| Playing career | |||||||||||

| 1949–1953 | Kansas | ||||||||||

| Coaching career (HC unless noted) | |||||||||||

| 1953–1955 | Kansas (assistant) | ||||||||||

| 1955–1958 | Air Force (assistant) | ||||||||||

| 1958–1961 | North Carolina (assistant) | ||||||||||

| 1961–1997 | North Carolina | ||||||||||

| Head coaching record | |||||||||||

| Overall | 879–254 (.776) | ||||||||||

| Accomplishments and honors | |||||||||||

| Championships | |||||||||||

As a coach

NCAA Division I Tournament (1952) | |||||||||||

| Awards | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Basketball Hall of Fame Inducted in 1983 | |||||||||||

| College Basketball Hall of Fame Inducted in 2006 | |||||||||||

Medal record

| |||||||||||

Smith was best known for running a clean program and having a high graduation rate, with 96.6% of his athletes receiving their degrees.[3][4] While at North Carolina, Smith helped promote desegregation by recruiting the university's first African-American scholarship basketball player, Charlie Scott, and pushing for equal treatment for African Americans by local businesses.[5] Smith coached and worked with numerous people at North Carolina who achieved notable success in basketball, as players, coaches, or both. Smith retired in 1997, saying that he was not able to give the team the same level of enthusiasm that he had given it for years. After retiring, Smith used his influence to help various charitable ventures and liberal political activities, but in his later years he suffered from advanced dementia and ceased most public activities.[6]

Biography

Early years

Smith was born in Emporia, Kansas, on February 28, 1931.[7][8] Both of his parents were public school teachers.[7] Smith's father, Alfred, coached the Emporia High Spartans basketball team to the 1934 state title in Kansas.[7] This 1934 team was notable for having the first African American basketball player in Kansas tournament history.[7] While at Topeka High School, Smith lettered in basketball all four years and was named all-state in basketball as a senior.[7][9] Smith's interest in sports was not limited to basketball. Smith also played quarterback for his high school football team and catcher for the high school baseball team.[9]

College years

After graduating from high school, Smith attended the University of Kansas on an academic scholarship. He majored in mathematics and joined Phi Gamma Delta fraternity.[9][10] While at Kansas, Smith continued his interest in sports by playing varsity basketball, varsity baseball, and freshman football. He was also a member of the Air Force ROTC detachment. During his time on the varsity basketball team, Kansas won the national championship in 1952. In 1953, the team was an NCAA tournament finalist.[9][10] Smith's basketball coach during his time at Kansas was Phog Allen, who had been coached at the University of Kansas by the inventor of basketball, James Naismith.[10] After graduation, Smith served as assistant coach at Kansas in the 1953–54 season.[11]

Coaching career

Early years in basketball coaching

Smith was commissioned as a second lieutenant on June 7, 1954, in the United States Air Force and was stationed at Fürstenfeldbruck Air Base in Germany where he was on a team that won the Air Force championship for Europe.[12] He later worked as a head coach of United States Air Force Academy's baseball and golf teams.[11] Yet, Smith's big break would come in the United States. In 1958, North Carolina coach Frank McGuire asked Smith to join his staff as an assistant coach.[11] Smith served under McGuire for three years until 1961, when McGuire was forced to resign by Chancellor William Aycock in the wake of a major recruiting scandal, and consequently, an NCAA mandated probation.

Years later, Aycock recalled that McGuire came to his office on a Saturday and told him he was resigning. Smith was waiting in McGuire's car outside South Building (UNC's main administration building), so Aycock called him in and asked him if he wanted to take over as head coach. Smith accepted, and the hiring was formally announced the following Monday.[13] When Aycock named Smith as head coach, he told the 30-year-old Smith that wins and losses didn't matter as much as running a clean program and representing the university well. [14]

The Atlantic Coast Conference (ACC) had canceled the Dixie Classic, an annual basketball tournament in Raleigh, North Carolina, due to a national point-shaving scandal including a North Carolina player (Lou Brown).[15] As a result of the scandal, North Carolina de-emphasized basketball by cutting their regular-season schedule. In Smith's first season, North Carolina played only 17 games and went 8–9.[11][16] This was the only losing season he endured during his career.[17] In 1965, he was famously hanged in effigy on the university campus following a disappointing loss to Wake Forest.[11] After that game, UNC would win nine of their last eleven games,[18] and Smith would subsequently go on to turn the program into a consistent success. From 1965 to 1966 onward, Smith's teams never finished worse than tied for third in the ACC.[19] For the first 21 of those years, they did not finish worse than a tie for second. By comparison, during that time the ACC's other charter members each finished last at least once.

Smith's first major successes came in the late 1960s, when his teams won consecutive regular-season and ACC tournament championships, and went to three straight Final Fours, going all the way to the national championship game in 1968. They would appear in either the NCAA or NIT in every one of Smith's final 31 years in Chapel Hill. However, this run occurred in the middle of UCLA's stretch of 10 titles in 12 years, and in fact Smith lost to UCLA's John Wooden in the 1968 title game.

First national championship

Smith's first national championship occurred with his 1981–82 team, which was composed of future NBA players such as Michael Jordan, James Worthy and Sam Perkins.[20] After winning the NCAA Tournament, North Carolina had a record of 32–2.[21] The other teams that advanced with North Carolina were Georgetown, Houston and Louisville. The Tar Heels actually finished in a tie for first in the ACC regular season with the Ralph Sampson-led Virginia Cavaliers. In the semifinals, North Carolina defeated Houston 68–63 in New Orleans, while Georgetown defeated Louisville 50–46.

The national title game against Georgetown was evenly matched throughout. However, with 17 seconds left on the clock, and the Tar Heels behind by 1 point, Jordan made what ended up being the game-winning shot to put the Tar Heels up 63–62. On Georgetown's ensuing possession, Hoya guard Fred Brown inexplicably passed the ball directly to Worthy with no Georgetown player anywhere near the pass. Worthy attempted to dribble out the clock, but was fouled with 2 seconds left. He missed both free throws, but Georgetown had no timeouts left. The Hoyas missed a halfcourt shot as time expired, giving Smith his first national championship in his seventh appearance in the Final Four.

Second national championship

Dean Smith's 1992–93 squad featured George Lynch, Eric Montross, Brian Reese, Donald Williams, and Derrick Phelps. The Tar Heels started out with an 8–0 record and were ranked #5 in the country when they met #6 Michigan in the semi-finals of the Rainbow Classic. The Wolverines, led by the Fab Five in their sophomore season, won 79–78 on a last-second shot. North Carolina bounced back with nine straight wins before losing back-to-back road games against unranked Wake Forest and #5 Duke. After seven more straight wins, the Tar Heels were ranked #1 heading into the last week of the regular season (their first #1 ranking since the start of the 1987–88 season). North Carolina beat #14 Wake Forest and #6 Duke to close out the regular season and clinch the top seed in the ACC tournament. North Carolina reached the tournament final, but they lost 77–75 to Georgia Tech without Derrick Phelps, who was injured. Nonetheless, North Carolina was awarded the top seed in the East Regional of the NCAA tournament, defeating #16-seed East Carolina (85-65), #8-seed Rhode Island (112-67), #4-seed Arkansas (80-74) and #2-seed Cincinnati (75-68) to reach the Final Four in New Orleans.

In the National Semifinals, Smith's Tar Heels defeated his alma mater Kansas (coached by future North Carolina coach Roy Williams) 78–68. In 1991, the same two teams also met in the National Semifinals with Kansas prevailing and Dean Smith being ejected. The 1993 victory for UNC set up a rematch from earlier that season with #3-ranked Michigan in the Finals.

The 1993 national title game was a see-saw battle throughout, but is remembered best for Chris Webber calling a time-out while trapped against the sideline by two defenders. Michigan did not have any timeouts remaining and trailed by two points. Michigan was assessed a technical foul and North Carolina ended up winning 77–71, giving Smith his second national championship.[22] After a six-year investigation by the NCAA, Webber's association and financial dealings with Ed Martin determined that there had been a series of violations and direct payments to players and was termed "the University of Michigan basketball scandal" and resulted in Michigan pulling down all of its banners and titles from that era.

Retirement

Smith abruptly announced his retirement on October 9, 1997. He had said that if he ever felt he could not give his team the same enthusiasm he had given it for years, he would retire.[23] His announcement was unexpected, as he had given little warning that he was considering retirement.[24] With such short notice of Smith's retirement, Bill Guthridge, who had been his assistant for 30 years, succeeded him as head coach.

During his retirement, Smith had a large influence on the North Carolina basketball program. In 2003 Smith talked to Roy Williams regarding his decision about whether or not to replace a struggling Matt Doherty as head coach.[25] Williams had previously declined the head coaching position three years earlier when Guthridge retired.[26]

In July 2010, journalist John Feinstein disclosed that he had planned to write a biography of Smith, but had to shelve it due to Smith's deteriorating memory.[27] Shortly after, Smith's family released a letter stating that he had a "progressive neurocognitive disorder", which had not been publicly disclosed as Alzheimer's or anything else. He had trouble remembering the names of some of his players, the letter said, but he could not forget what his relationships with those players meant. He also remembered words to hymns and jazz standards, but did not go to concerts. He had difficulty with traveling but continued to watch his former team on TV. Williams said, "He does have his good days and bad."[28]

Coaching profile

Smith-coached teams varied in style, depending on the players Smith had available. But they generally featured a fast-break style, a half-court offense that emphasized the passing game, and an aggressive trapping defense that produced turnovers and easy baskets. From 1970 until his retirement, his teams featured a shooting percentage of over 50% in all but four years.

Smith was credited with creating or popularizing the following basketball techniques: The "tired signal," in which a player would use a hand signal (originally a raised fist) to indicate that he needed to come out for a rest,[29][30] huddling at the free throw line before a foul shot,[29][30] encouraging players who scored a basket to point a finger at the teammate who passed them the ball, in honor of the passer's selflessness,[29][30] instituting a variety of defensive sets in one game,[29][31] having the point guard call out the defense set for the team,[29][31] and creating a number of defensive sets, including the point zone, the run-and-jump, and double-teaming the screen-and-roll.[9]

Strategically, Smith was most associated with his implementation of John McLendon's four corners offense, a strategy for stalling with a lead near the end of the game. Smith's teams executed the four corners set so effectively that in 1985 the NCAA instituted a shot clock to speed up play and minimize ball-control offense.[9][32] Although fellow Kansas alum McLendon actually invented the four corners offense, Smith got credit for utilizing it in games.[29] Smith was also the author of Basketball: Multiple Offense and Defense, which is the best-selling technical basketball book in history.[2]

Smith also instituted the practice of starting all his team's seniors on the last home game of the season ("Senior Day") as a way of honoring the contributions of the substitutes as well as the stars.[33] In a season when the team included six seniors, he put all six on the floor at the beginning of the game – drawing a technical foul – rather than leave one of them out.[34]

During the 1993 run for the national title, Smith used a method that was introduced to him at a conference in Switzerland. At the conference, Smith was presented a tape by a lecturer who used doctored images to achieve his goal of losing weight. The photos showed the lecturer what he would look like if he were thinner as motivation to reach his weight-loss goals. Smith took a picture of the scoreboard from the 1982 Championship, modified it to read 1993 and erased the name Georgetown, leaving that space blank. He proceeded to place copies of the doctored photo in all of the players' lockers.[22]

Student athletes under Smith achieved a graduation rate of 96.6% at North Carolina,[3][4] and he established a reputation for running a clean program.[35]

Personal life

Smith married Ann Cleavinger in 1954, shortly before his deployment overseas with the United States Air Force. They had three children: daughters Sharon and Sandy, and son Scott. Smith and Cleavinger divorced in 1973. Smith married psychiatrist Linnea Weblemoe Smith on May 21, 1976. They have two adult daughters, Kristen and Kelly.[36] Weblemoe Smith would battle Playboy over college all-star teams, "campaigning for an end of all sports associations with Playboy, to include all interviews as well as the regular picture-taking of top college basketball and football stars".[37]

Death

Dean Smith died on the evening of February 7, 2015, at age 83, at his Chapel Hill home surrounded by his family.[38] A private funeral was held on February 12 at Binkley Baptist Church in Chapel Hill, with burial following at Old Chapel Hill Cemetery on the UNC campus.[39] A public memorial service was held at the Dean Smith Center on February 22.[39]

He willed a $200 check to each of the former lettermen he coached during his 36 years at North Carolina, which included the message "Enjoy a dinner out compliments of Coach Dean Smith.” The trustee told ESPN that checks were sent out to about 180 ex-players.[40]

Accomplishments and recognition

Accomplishments

Among the accomplishments of Smith:

- 879 wins in 36 years of coaching, 5th most in men's college Division I basketball history behind Mike Krzyzewski, Jim Boeheim, Roy Williams and Bob Knight, and the most wins of any coach at the time of his retirement.

- 77.6% winning percentage, which puts him 9th on highest winning percentage.[1]

- Fourth total number of college games coached with 1,133.[1]

- Most Division I 20-win seasons, with 27 consecutive 20-win seasons from 1970 to 1997[3] and 30 20-win seasons total.[1]

- 22 seasons with at least 25 wins

- 35 consecutive seasons with a 50% or better record.[3]

- Two national championships (1982, 1993)

- 11 Final Fours (behind Krzyzewski's 13 and John Wooden's 12).[3]

- 17 regular-season ACC titles, plus 33 straight years finishing in the conference's top three and 20 years in the top two

- 13 ACC tournament titles

- 31 consecutive appearances in either the NCAA Tournament or NIT from 1967 to 1997

- 27 NCAA tournament appearances, including 23 consecutive from 1975 to 1997[3]

- Recruited 26 All-Americans to play at North Carolina under him.[3]

- His players were often successful in the NBA. Five of Smith's players have been Rookie of the Year in either the NBA or ABA. Among Smith's most successful players in the NBA are Michael Jordan, Larry Brown, James Worthy, Sam Perkins, Phil Ford, Bob McAdoo, Billy Cunningham, Kenny Smith, Walter Davis, Al Wood, Jerry Stackhouse, Antawn Jamison, Rick Fox, Vince Carter, Brad Daugherty, Charlie Scott and Rasheed Wallace. Smith coached 25 NBA first round draft picks.[3] When Jordan was inducted into the Basketball Hall of Fame, he said, "There's no way you guys would have got a chance to see Michael Jordan play without Dean Smith."

- In 1976, Smith coached the United States team to a gold medal at the Summer Olympics in Montreal.

- Smith was one of only three coaches to have coached teams to an Olympic gold medal, an NIT championship and an NCAA championship.[3] The others are Pete Newell and Bob Knight.

- At the time of his retirement, Smith was one of only two people, along with Bob Knight, who had played on and coached a winning NCAA championship basketball team.

Recognition

Smith received a number of personal honors during his coaching career. He was named the National Coach of the Year four[citation needed] times (1977, 1979, 1982, 1993) and ACC Coach of the Year eight times (1967, 1968, 1969, 1971, 1976, 1977, 1979, 1988, 1993). Smith was also inducted into the Basketball Hall of Fame on May 2, 1983, two years after being enshrined in the North Carolina Sports Hall of Fame.

Smith was the first recipient of the Mentor Award for Lifetime Achievement, given by the University of North Carolina Committee on Teaching Awards for "a broader range of teaching beyond the classroom."[4] He has also been awarded honorary doctorates by Eastern University and Catawba College.[41]

In 1982, Smith was the recipient of the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement presented by Awards Council member Coach Tom Landry.[42]

The basketball arena at North Carolina, the Dean Smith Center, was named for Smith. It is also widely referred to as the "Dean Dome." Smith coached the last 11.5 years of his career in the arena, making him one of the few college coaches to have coached in an arena or stadium named for him. In 1997, upon his retirement, Smith was named Sportsman of the Year by the magazine Sports Illustrated. ESPN named Smith one of the five all-time greatest American coaches of any sport. In 1998, he won the Arthur Ashe Courage Award, presented at the annual ESPY Awards hosted by ESPN.[43]

On November 17, 2006, Smith was recognized for his impact on college basketball as a member of the founding class of the National Collegiate Basketball Hall of Fame. He was one of five, along with Oscar Robertson, Bill Russell, John Wooden and Dr. James Naismith, selected to represent the inaugural class.[44] In 2007, he was enshrined in the FIBA Hall of Fame.[45]

On November 20, 2013, President Barack Obama awarded Smith the Presidential Medal of Freedom.[46]

On December 8, 2021, the North Carolina State Board of Transportation approved naming Interstate 40 between U.S. 15-501 and North Carolina Highway 54 "Dean Smith Highway".[47]

Political activities

A longtime Democrat, Dean Smith was one of the most prominent liberals in North Carolina politics. Politically, he was best known for promoting desegregation. In 1964, Smith joined a local pastor and a black North Carolina theology student to integrate The Pines, a Chapel Hill restaurant. He also integrated the Tar Heels basketball team by recruiting Charlie Scott as the university's first black scholarship athlete.[5] In 1965, Smith helped Howard Lee, a black graduate student at North Carolina, purchase a home in an all-white neighborhood.[9] He opposed the Vietnam War and, in the early 1980s, famously recorded radio spots to promote a freeze on nuclear weapons. He has been a prominent opponent of the death penalty. In 1998, he appeared at a clemency hearing for a death-row inmate and pointed at then-Governor Jim Hunt: "You're a murderer. And I'm a murderer. The death penalty makes us all murderers." As head coach, he periodically held North Carolina basketball practices in North Carolina prisons.[48]

While coach, he was recruited by some in the Democratic Party to run for the United States Senate against incumbent Jesse Helms. He declined. But in retirement, he continued to speak out on issues such as the Iraq War, death penalty, and gay rights.[48][dead link][49] Although a staunch Democrat, Smith did support one of his former players, Richard Vinroot, a Republican who ran for governor of North Carolina in 2000.[50][51] In 2006, Smith became the spokesperson for Devout Democrats, an inter-faith, grassroots political action committee designed to convince religious Americans to vote for Democrats. Smith was featured in an ad that ran in newspapers across North Carolina and was featured in an Associated Press article.[52] On October 13, 2008, he endorsed Senator Barack Obama's candidacy for President of the United States.[53]

Coaching tree

One hallmark of Dean Smith's tenure as coach was the concept of the "Carolina Family," the idea that anyone associated with the program was entitled to the support of others. Many of his former players and coaching staff became successful basketball coaches and executives.[54] Smith's coaching tree includes:

- Larry Brown, a former Smith player; former coach of the Denver Nuggets, New York Knicks, San Antonio Spurs, Indiana Pacers, Philadelphia 76ers, Charlotte Bobcats; winner of championships in both the NBA (Detroit Pistons) and college (Kansas). Current assistant at Memphis Tigers.

- Scott Cherry, former Smith player and former women's assistant coach at Middle Tennessee State University. Former head coach at High Point University, also former assistant coach at Western Kentucky University and South Carolina.

- Billy Cunningham, coach of the 1983 NBA champion Philadelphia 76ers

- Hubert Davis, current head coach at North Carolina.

- Matt Doherty, former Smith player. Former head coach at Notre Dame, North Carolina, Florida Atlantic University, and SMU; also a former assistant under Roy Williams at Kansas.

- George "Butch" Estes, head coach at Palm Beach State College (Lake Worth, FL)

- Eddie Fogler, National Coach of the Year at both Vanderbilt and South Carolina, also former head coach at Wichita State University

- Phil Ford, former assistant coach of the Charlotte Bobcats and UNC

- Bill Guthridge, Smith's former assistant coach and former UNC head coach; National Coach of the Year at UNC

- Dave Hanners, former assistant coach of the Charlotte Bobcats, Detroit Pistons, Philadelphia 76ers and New York Knicks. Currently assistant coach of the New Orleans Pelicans.

- George Karl, a point guard under Smith, former head coach of the Cleveland Cavaliers, Golden State Warriors, Real Madrid, Seattle SuperSonics, Milwaukee Bucks, Denver Nuggets and Sacramento Kings.

- John Kuester, former head coach of the Detroit Pistons

- Mitch Kupchak, current general manager of the Charlotte Hornets

- Jeff Lebo, former head coach at East Carolina, Tennessee Tech, Chattanooga, and Auburn. Current assistant for the Tar Heels.

- Doug Moe, former NBA coach (Denver Nuggets) and NBA Coach of the Year Award winner

- Mike O'Koren, assistant head coach of the Philadelphia 76ers

- Buzz Peterson, previously head coach at UNC Wilmington, Coastal Carolina, Tennessee, Tulsa and Appalachian State; and director of player personnel with the Charlotte Hornets

- Brian Reese, current head coach at Georgian Court University

- King Rice, current head coach at Monmouth; former assistant at Oregon, Illinois State, Providence and Vanderbilt University

- Tony Shaver, former head coach at the College of William & Mary

- Jerry Stackhouse, played for Smith at UNC, former assistant coach of the Toronto Raptors and Memphis Grizzlies, current head coach at Vanderbilt

- Pat Sullivan, former assistant coach of the Detroit Pistons. Director of recruiting for the Tar Heels.

- Rasheed Wallace, former assistant coach of the Detroit Pistons, former head coach of Charles E. Jordan High School. Current assistant at Memphis Tigers.

- Roy Williams, former University of Kansas coach and North Carolina assistant, former North Carolina head coach

- Ettore Messina, current assistant coach for the San Antonio Spurs, used to be Dean Smith's interpreter at his basketball clinics in Italy.

Smith was part of the coaching tree of James Naismith, by way of playing under Phog Allen at Kansas.

Head coaching record

| Season | Team | Overall | Conference | Standing | Postseason | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North Carolina Tar Heels (Atlantic Coast Conference) (1961–1997) | |||||||||

| 1961–62 | North Carolina | 8–9 | 7–7 | T–4th | |||||

| 1962–63 | North Carolina | 15–6 | 10–4 | 3rd | |||||

| 1963–64 | North Carolina | 12–12 | 6–8 | 5th | |||||

| 1964–65 | North Carolina | 15–9 | 10–4 | T–2nd | |||||

| 1965–66 | North Carolina | 16–11 | 8–6 | T–3rd | |||||

| 1966–67 | North Carolina | 26–6 | 12–2 | 1st | NCAA University Division Final Four | ||||

| 1967–68 | North Carolina | 28–4 | 12–2 | 1st | NCAA University Division Runner-up | ||||

| 1968–69 | North Carolina | 27–5 | 12–2 | 1st | NCAA University Division Final Four | ||||

| 1969–70 | North Carolina | 18–9 | 9–5 | T–2nd | NIT First Round | ||||

| 1970–71 | North Carolina | 26–6 | 11–3 | 1st | NIT Champion | ||||

| 1971–72 | North Carolina | 26–5 | 9–3 | 1st | NCAA University Division Final Four | ||||

| 1972–73 | North Carolina | 25–8 | 8–4 | 2nd | NIT Semifinals | ||||

| 1973–74 | North Carolina | 22–6 | 9–3 | T–2nd | NIT First Round | ||||

| 1974–75 | North Carolina | 23–8 | 8–4 | T–2nd | NCAA Division I Second Round | ||||

| 1975–76 | North Carolina | 25–4 | 11–1 | 1st | NCAA Division I First Round | ||||

| 1976–77 | North Carolina | 28–5 | 9–3 | 1st | NCAA Division I Runner-up | ||||

| 1977–78 | North Carolina | 23–8 | 9–3 | 1st | NCAA Division I First Round | ||||

| 1978–79 | North Carolina | 23–6 | 9–3 | 1st | NCAA Division I Second Round | ||||

| 1979–80 | North Carolina | 21–8 | 9–5 | T–2nd | NCAA Division I Second Round | ||||

| 1980–81 | North Carolina | 29–8 | 10–4 | 2nd | NCAA Division I Runner-up | ||||

| 1981–82 | North Carolina | 32–2 | 12–2 | T–1st | NCAA Division I Champion | ||||

| 1982–83 | North Carolina | 28–8 | 12–2 | T–1st | NCAA Division I Elite Eight | ||||

| 1983–84 | North Carolina | 28–3 | 14–0 | 1st | NCAA Division I Sweet Sixteen | ||||

| 1984–85 | North Carolina | 27–9 | 9–5 | T–1st | NCAA Division I Elite Eight | ||||

| 1985–86 | North Carolina | 28–6 | 10–4 | 3rd | NCAA Division I Sweet Sixteen | ||||

| 1986–87 | North Carolina | 32–4 | 14–0 | 1st | NCAA Division I Elite Eight | ||||

| 1987–88 | North Carolina | 27–7 | 11–3 | 1st | NCAA Division I Elite Eight | ||||

| 1988–89 | North Carolina | 29–8 | 9–5 | T–2nd | NCAA Division I Sweet Sixteen | ||||

| 1989–90 | North Carolina | 21–13 | 8–6 | T–3rd | NCAA Division I Sweet Sixteen | ||||

| 1990–91 | North Carolina | 29–6 | 10–4 | 2nd | NCAA Division I Final Four | ||||

| 1991–92 | North Carolina | 23–10 | 9–7 | 3rd | NCAA Division I Sweet Sixteen | ||||

| 1992–93 | North Carolina | 34–4 | 14–2 | 1st | NCAA Division I Champion | ||||

| 1993–94 | North Carolina | 28–7 | 11–5 | 2nd | NCAA Division I Second Round | ||||

| 1994–95 | North Carolina | 28–6 | 12–4 | T–1st | NCAA Division I Final Four | ||||

| 1995–96 | North Carolina | 21–11 | 10–6 | 3rd | NCAA Division I Second Round | ||||

| 1996–97 | North Carolina | 28–7 | 11–5 | 2nd | NCAA Division I Final Four | ||||

| North Carolina: | 879–254 (.776) | 364–136 (.728) | |||||||

| Total: | 879–254 (.776) | ||||||||

|

National champion

Postseason invitational champion

| |||||||||

See also

- List of college men's basketball coaches with 600 wins

- List of NCAA Division I Men's Final Four appearances by coach

Notes

- a Smith's record of 879 victories was surpassed by Bob Knight in 2007, and Mike Krzyzewski in 2011. More information on the current leaders for the total number of victories for men's basketball coaches can be found at List of college men's basketball coaches with 600 wins.

Further reading

- Dean Smith, John Kilgo, Sally Jenkins: A Coach's Life. My 40 years in college basketball. New York 2002, ISBN 0-375-75880-1

- Dean Smith, Gerald D. Bell, John Kilgo, Roy Williams: The Carolina Way: Leadership Lessons from a Life in Coaching, ISBN 0-14-303464-2

- Dean Smith: Basketball: Multiple Offense and Defense, ISBN 0-205-29119-8

- David Scott: Quotable Dean Smith: Words of Insight, Inspiration, and Intense Preparation by and about Dean Smith, the Dean of College Basketball Coaches., ISBN 1-931249-27-X

- Art Chansky: Dean's Domain: The Inside Story of Dean Smith and His College Basketball Empire, ISBN 1-56352-540-2

- Art Chansky: The Dean's List: A Celebration of Tar Heel Basketball and Dean Smith, ISBN 0-446-52007-1

- Ken Rosenthal Dean Smith: A Tribute, ISBN 1-58261-003-7

References

- "NCAA stats". NCAA. NCAA. Archived from the original on October 8, 2006. Retrieved February 1, 2007.

- "Dean Smith Biography". Hall of Famers. Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame, Inc. Archived from the original on May 5, 2007. Retrieved October 29, 2006.

- "Smith by the Numbers". Sports Illustrated. Dean Smith: The 1997 Sports Illustrated Sportsman of the Year. Archived from the original on May 24, 2006. Retrieved October 29, 2006.

- Andrea Beloff (April 20, 1998). "Dean Smith recognized for lifetime achievement in and outside classroom". University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill News Services. Archived from the original on November 17, 2007. Retrieved October 29, 2006.

- "ACC 50th Anniversary Team". NBA.com. Archived from the original on December 2, 2009. Retrieved October 29, 2006.

- "Precious Memories". ESPN.com. Archived from the original on March 6, 2014. Retrieved March 5, 2014.

- Wolff, Alexander. "Growing Up, 1931–49". Sports Illustrated. Dean Smith: The 1997 Sports Illustrated Sportsman of the Year. Archived from the original on September 12, 2004. Retrieved October 29, 2006.

- "Smith, Dean E." Kansas Sports Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved October 29, 2006.

- Mike Puma (May 18, 2006). "The Dean of College Hoops". ESPN. Archived from the original on October 10, 2008. Retrieved October 29, 2006.

- Wolff, Alexander. "College Years, 1949–53". Sports Illustrated. Dean Smith: The 1997 Sports Illustrated Sportsman of the Year. Archived from the original on December 18, 2005. Retrieved August 16, 2006.

- Wolff, Alexander. "Starting Out, 1953–65". Sports Illustrated. Dean Smith: The 1997 Sports Illustrated Sportsman of the Year. Archived from the original on April 9, 2005. Retrieved October 29, 2006.

- Davis, Jeff. Dean Smith: A Basketball Life, Rodale, Inc., New York, 2017, pages 65 and 73. ISBN 978-1-62336-360-4.

- Huffman, Diane. UNC chancellor recalls bold decision to hire Dean Smith. WNCN, February 8, 2015.

- Chansky, Art. Blue Blood:Duke-Carolina: Inside the Most Storied Rivalry in College Hoops. New York City: St. Martin's Press, 2006. ISBN 0-312-32787-0

- A.J. Carr (March 16, 2006). "Dixie Classic scandal left bad taste". The News & Observer. Archived from the original on March 11, 2007. Retrieved October 29, 2006.

- Adam Lucas (December 19, 2002). "Smith's First Five Teams To Reunite Tonight". Tar Heel Monthly. Archived from the original on March 23, 2007. Retrieved October 29, 2006.

- "In 36 seasons as North Carolina head coach, Dean Smith's only losing season was his first". Twitter. ESPN. February 8, 2015. Archived from the original on October 19, 2015. Retrieved February 8, 2015.

- Wolff, Alexander. "Installing the System, 1965–82". Sports Illustrated. Dean Smith: The 1997 Sports Illustrated Sportsman of the Year. Archived from the original on September 15, 2005. Retrieved October 29, 2006.

- Wolff, Alexander. "Breaking Through, 1982–1997". Sports Illustrated. Dean Smith: The 1997 Sports Illustrated Sportsman of the Year. Archived from the original on September 12, 2004. Retrieved October 29, 2006.

- Curry Kirkpatrick (April 5, 1982). "Nothing Can Be Finer". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on February 4, 2009. Retrieved August 5, 2007.

- Tarheel Monthly A Magical Season - Celebrating the 20th Anniversary of the 1982 NCAA Champs Archived August 18, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. Published March 2002. Retrieved on August 13, 2007.

- Adam Lucas (March 30, 2003). "THM: Looking Back At 1993". Tar Heel Monthly. Archived from the original on November 17, 2007. Retrieved August 8, 2007.

- "END OF AN ERA". Online NewsHour:Dean Smith Retires: October 9, 1997. PBS. October 9, 1997. Archived from the original on March 25, 2006. Retrieved October 29, 2006.

- Ensslin, Paul; Asher, Mark (October 9, 1997). "North Carolina Coach Dean Smith to Retire Today". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- "Goin' to the Chapel (Hill)". Sports Illustrated. April 14, 2003. Archived from the original on June 17, 2006. Retrieved October 29, 2006.

- Eddie Pells (November 9, 2003). "Williams still not thrilled about move". Lawrence Journal-World, 6News. Archived from the original on July 8, 2007. Retrieved October 29, 2006.

- John Feinstein (July 12, 2010). "Not wanting to break the story, I can now discuss Dean Smith". Archived from the original on July 15, 2010. Retrieved July 15, 2010.

- Pickeral, Robbi; Tomlinson, Tommy (July 17, 2010). "Dean Smith's disorder doesn't diminish his spirit". News and Observer. Archived from the original on July 19, 2010. Retrieved July 17, 2010.

- Wolff, Alexander. "The Father of Invention: Seven Innovations". Sports Illustrated. Dean Smith: The 1997 Sports Illustrated Sportsman of the Year. Archived from the original on January 3, 2007. Retrieved October 29, 2006.

- "The List: Best coaches". ESPN. Archived from the original on November 1, 2006. Retrieved October 29, 2006.

- Ken Lindsay. "Alternating Multiple Basketball Defenses". Archived from the original on November 1, 2006. Retrieved October 29, 2006.

- James A. Sheldon (June 16, 1982). "Basketball rules experiments may net results" (PDF). The NCAA News. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 13, 2006. Retrieved October 29, 2006.

- Bill Kwon (February 25, 1999). "Wallace to get honor that is long overdue". Sports Watch. Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Archived from the original on November 17, 2007. Retrieved October 29, 2006.

- Ryan Killian (January 1, 2006). "Dean Smith regarded as one of the best". The Daily Texan. Retrieved October 29, 2006.[dead link]

- Larivere, David (February 8, 2015). "Dean Smith, One Of The Greatest Innovators In College Basketball, Dead At 83". Forbes. Archived from the original on February 9, 2015.

- Smith, Dean (2002). A Coach's Life. New York: Random House.

- "Scouting; The Coach's Wife Battles Playboy". The New York Times. July 15, 1986. p. 24. Archived from the original on December 31, 2019. Retrieved December 31, 2019.

- "Carolina's Dean Smith passes away at age 83". www.unc.edu. Archived from the original on February 8, 2015. Retrieved February 8, 2015.

- "Loved ones mourn Dean Smith". ESPN.com. February 12, 2015. Archived from the original on February 13, 2015. Retrieved February 13, 2015.

- "Dean Smith willed $200 to each of his former lettermen". www.msn.com. Archived from the original on March 28, 2015. Retrieved March 26, 2015.

- "Dean E. Smith Term Professorship". University of North Carolina Chapel Hill. March 15, 2005. Archived from the original on June 9, 2007. Retrieved July 28, 2007.

- "Golden Plate Awardees of the American Academy of Achievement". www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement.

- "ESPY Awards past winners". ESPN. Archived from the original on October 13, 2006. Retrieved October 18, 2006.

- "Collegiate Basketball Hall of Fame to induct founding class". NABC. Archived from the original on November 17, 2007. Retrieved November 20, 2006.

- "Dean Smith, Bill Russell inducted into FIBA Hall of Fame - USATODAY.com". usatoday.com. Archived from the original on February 8, 2015. Retrieved February 8, 2015.

- Rush the Court. "Dean Smith a deserving recipient of Presidential Medal of Freedom". SI.com. Archived from the original on February 8, 2015. Retrieved February 8, 2015.

- Stradling, Richard (December 8, 2021). "UNC's Dean Smith and Roy Williams are immortalized on Triangle highway". News & Observer.

- Rick Reilly (March 17, 2003). "A Man of Substance". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on October 14, 2006. Retrieved October 29, 2006.

- Bonnie DeSimone (February 9, 2003). "Ex-coach takes on a higher cause North Carolina basketball legend Dean Smith is working to end the death penalty in his state". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on November 30, 2005. Retrieved October 29, 2006.

- "Biography for Dean Smith (II)". IMDB. Archived from the original on August 11, 2013. Retrieved October 29, 2006.

- Mark Wineka (August 11, 2000). "Vinroot raises funds, stresses Republicans' need for diversity". Salisbury Post. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved October 29, 2006.

- "UNC's Dean Smith featured in ad for 'Devout Democrats'". News and Observer (Raleigh). Associated Press. October 6, 2006. Retrieved October 29, 2006.[dead link]

- Montopoli, Brian (October 13, 2008). "Your Move, Krzyzewski: Dean Smith Backs Obama". Horserace. CBS News. Archived from the original on October 14, 2008. Retrieved October 14, 2008.

- Alexander, Chip (February 8, 2015). "Legendary UNC coach Dean Smith dies at 83". News & Observer. Archived from the original on February 10, 2015. Retrieved February 8, 2015.

External links

- Dean Smith at the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame

- Dean Smith at Find a Grave

На других языках

- [en] Dean Smith

[es] Dean Smith

Dean Edwards Smith (Emporia, Kansas; 28 de febrero de 1931-Chapel Hill, Carolina del Norte; 7 de febrero de 2015) fue un entrenador y jugador de baloncesto estadounidense.[ru] Смит, Дин (баскетболист)

Дин Эдвардс Смит (англ. Dean Edwards Smith; 28 февраля 1931, Эмпория, Канзас — 7 февраля 2015) — американский баскетбольный тренер. Зал славы баскетбола назвал его «Легендарным тренером». 36 лет он тренировал в Университете Северной Каролины в Чапел-Хилле. Смит тренировал с 1961 по 1997 год и ушел на пенсию с 879 победами, что было в то время мужским баскетбольным рекордом в NCAA Дивизиона I. У Смита был 9-й самый высокий процент побед среди тренеров по баскетболу в колледже (77,6 %). За время своего пребывания на посту главного тренера, Северная Каролина выиграла два национальных чемпионата и появлялась 11 раз в Финалах четырех[1]. Смит играл в баскетбол в университете Канзаса, где он выиграл Национальный Чемпионат в 1952 году, играя под руководством тренера Зала славы, Фога Аллена.Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии